“In my unloveliness I plunged into the lovely things which you created. You were with me, but I was not with you. Created things kept me from you; yet if they had not been in you they would not have been at all. You called, you shouted, and you broke through my deafness. You flashed, you shone, and you dispelled my blindness. You breathed your fragrance on me; I drew in breath and now I pant for you. I have tasted you, now I hunger and thirst for more.” – St. Augustine

“Christ has created you because He wanted you. I know what you feel – terrible longing with dark emptiness. And yet He is the one in love with you.” – St. Teresa of Calcutta in a letter to Malcom Muggeridge

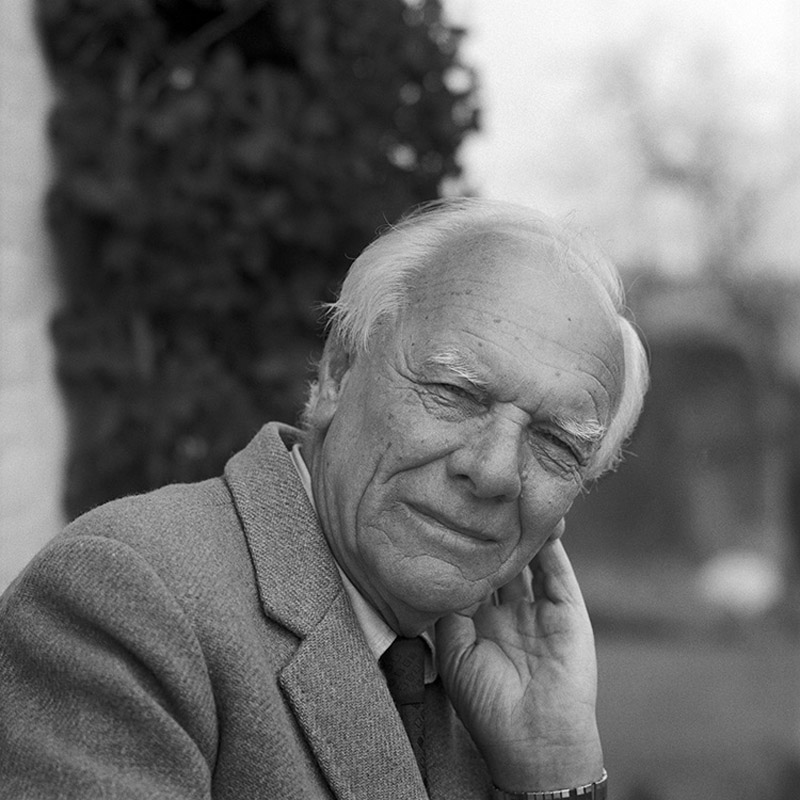

Generally speaking, modern people choose their religion so as to conform to the lives they are living. They believe as they live, rather than live as they believe. This attempt to quiet their consciences can seem like a brave act of individual liberty in a society that glories in religious pluralism. But in a more Christian age, men did not deny the incongruity of their faith with the follies of their own lives. They knew that truth wasn’t going to change to suit them, and they forced themselves to live with the tension in the hopes that one day they would reform. Malcom Muggeridge was this pre-modern type of man. He lived badly for many years, but God refused to permit him the illusions modern men seem to enjoy.

The outline of Muggeridge’s life is well known. The son of a middle-class Fabian socialist, Malcom became impatient with the gradualism and hypocrisy of a socialist elite that didn’t have the stomach for revolution and, despite lip-service paid to egalitarianism and the plight of the working class, enjoyed lives of globe-trotting luxury and indulgence. He became a staunch communist and an open admirer of the Soviet Union. Upon graduation from Cambridge he traveled to India where he taught in the colonial schools, studied Hinduism and Islam, sympathized with Ghandi, and promoted Indian nationalism. Returning to England, he found work as a journalist and was assigned foreign correspondent to Moscow by the Manchester Guardian. He relished the opportunity to see Soviet communism up close. But what he learned in this revered “worker’s paradise” turned his enthusiasm into horror. Despite his own rhetorical excesses, Malcom discovered in himself a fierce hatred of cruelty and injustice. The barbaric inhumanity he witnessed in the name of atheistic communism turned him against every kind of mass ideological movement. He was furthermore aghast at the calculated dishonesty and, in some cases, the self-delusion of the Western intelligentsia when it came to the Soviet Union, upon which they projected their hopes and aspirations. It was also clear to him that these westerners relied upon the “success” of Marxism-Leninism for their reputations.

Malcom was the first to break the story of the Stalinist famine in the Ukraine, wherein four million perished by starvation and disease while their food – not only grain, but the food in every pantry! – was hauled away to feed more cooperative Russians. Those who resisted, or who were suspected of resistance, were simply shot. To keep the word from getting out, the border was sealed so that Ukrainians had no escape. On a clandestine and unauthorized trip to the Ukraine, Malcom watched starving peasants being loaded onto cattle trucks at gunpoint with their hands bound behind their backs. The story was censored at first, but Malcom would not be silent and became an implacable foe of communism for the rest of his life.

This courageous but unpopular act nearly cost Malcom his career. Still a man of the political Left, by this time the Left would no longer have him. He was barely employable as a journalist in England in all but the most pro-establishment Tory publications (which he detested politically) and gossip columns. His family struggled as he tried to pay the bills with various desperate writing gigs. The war came and he joined the armed forces as an intelligence officer, serving honorably. He returned to England and, by a series of unlikely employments and promotions, ended up a media star himself, landing finally at the BBC. During this time his politics moved further away from those of any party and developed into something that resembled a pragmatic libertarianism. He was clearly a gifted wordsmith, a master of the language, and an incisive commentator. The quality of his writing was recognized as superb. He was surprisingly adaptable as a compelling television presence. Malcom became widely respected – and also reviled – for his piercing criticism of those in positions of power and authority. His transparent sincerity was part of his appeal, once admitting “I hate government. I hate power. I think that man’s existence, insofar as he achieves anything, is to resist power, to minimize power, to devise systems of society in which power is the least exerted.” Toward the end of his career his wit, humor, and voice were known to all Englishman. His highly televised face was recognized everywhere.

And yet, beneath all of this worldly success, Malcom had long been miserable.

Malcom read the Bible secretly as a child, enthralled with the Christ-figure. While at Cambridge he embraced the religious skepticism of the day, but found himself drawn to mystics and even to the devout. His best friend was a serious Christian who became an Anglican clergyman. Malcom especially admired his asceticism and religious discipline. At the same time Malcom had fallen into the casual homosexuality of the elite, a phenomenon that was rife in England at the time, though he was still in love with a girl back home. (The extent to which casual male homosexuality was a staple of upper class English life has always eluded me, but it seems to have been ubiquitous for several generations even as it remained illegal. This must have had severe psychological effects on many of its practitioners.) His passions became unruly, particularly his sexual passions. When he married Kitty Dobbs, as good Fabian socialists they seriously considered having an “open marriage”. It might as well have been. Malcom’s sordid infidelities are too numerous to count; Kitty’s are less numerous but no less tragic. This compulsive behavior went on for decades, all through the highs and lows of his career. It always left him feeling empty, despairing, and lost. He and Kitty fought bitterly and constantly. As his family grew, he sought escape in projects that took him far from home. He attempted suicide at least once. He agonized over religious questions, and though he couldn’t bring himself to believe, he couldn’t bring himself to reject God altogether either.

Part of Malcom’s inner torment was his self-image as a permanent outsider. Painful in his youth, he tried hard to belong without success. Later he came to see his outsider status as having important advantages. He was in that sense a free man. As a writer he could say what he wanted to say, without worrying about who it might offend. He relished attacking the “establishment” and its acolytes, but extended his range of targets to anyone whom he felt exercised undue influence over others. Maintaining this posture required a spirit that lacked generosity. He was outside by choice now, and developed a sort of contempt for insiders. This gave him his freedom. Insiders are not free: they have to bow to their institutions and defend their absurdities. Or so Malcom thought. As applied to the Church, Malcom could not see himself accepting a set of doctrines that were above criticism or deferring to churchmen who were, in his estimation, just party men like all the others. The extreme patriotism after the war ended turned him off for similar reasons. You would never find Malcom Muggeridge waving a flag or a pom-pom. But his independence came at the price of arrogance, to the point where, after his acceptance of the Christian faith, he could no longer stand to watch himself on television, deploring this “terrible man” with a “certain arrogance about myself” and “completely lacking in humility”.

Malcom’s exceptional intelligence, energy, and productivity was driven by a force he didn’t understand. The sheer volume impresses – books, plays, documentaries, interviews, hundreds of articles. He interviewed everyone from Churchill to MacArthur to Stalin’s daughter. His literary circles included all the men of letters of his time, being closest to George Orwell. He described his friend Graham Greene as a “saint who is trying unsuccessfully to be a sinner”; Hilaire Belloc as “not at all a serene man” nursing decades old grievances, and of whom, “having written about religion all of his life, there seemed to be very little in him”; and of Evelyn Waugh he said “I have formed the impression that he does not like me”, which was evidently true, although in fairness Waugh was a misanthrope who didn’t like anybody. Apart from Chesterton, whom he admired, the English Catholic literati did not impress Malcom as men whose Catholicism had changed them for the better. They left him curious but uninspired.

Behind the scenes of this busy public life was a titanic internal struggle between the flesh and the spirit. Even as Malcom gave in to the flesh, he would not surrender his mind. He began to see with increasing clarity how the ethos of liberalism had poisoned his own life, making himself and his loved ones miserable. What was previously a slow awakening became a torrent of awareness. He decried the comfortable materialism of his circumstances and longed for poverty and asceticism, for “the simple life”. He saw the rise of sexual promiscuity (with the implied dismissal of marriage), contraception, abortion, and euthanasia as signs of a decaying civilization with a Freudian death wish. He understood that the decline of Christian faith and respect for the Church was the source of these evils. He professed these insights publicly even as he continued to live according to his old habits.

Malcom plunged himself into research about this Jesus, this Man who haunted him all of his life and wouldn’t leave him any peace. The painful alienation and longing for God expressed in St. Augustine’s “Confessions” resonated with him acutely. He recalled with amazement the serene faith of the peasants he encountered in churches behind the iron curtain. He traveled to Lourdes and Palestine and was inspired by the faith of the Christian pilgrims, mostly of humble origins. He befriended a holy priest who ministered to the severely disabled. Finally, he sought out Mother Teresa, bewildered at this woman who accomplished so much with so little, who didn’t shrink from loving the unlovable, or touching the untouchable, and not for an idea or a set of abstract social principles, but for the love of a Person. The publicity-shy nun permitted him to make a television documentary about the works of her Missionaries of Charity, and to write a book about her – “Something Beautiful for God” – bringing her then obscure work to the attention of the world. Still unable to grasp Christ directly, Malcom was permitted to see Him through the life of a genuine saint, and in the faces of the world’s forgotten ones.

And then, in the twilight of his life, the old familiar pain of being an outsider looking in returned to him. He wanted what these Christians had, Who these Christians had, but didn’t know how to possess Him. He wanted to be counted among them, but still couldn’t bend the knee.

Malcom spent the remainder of his career defending and promoting a Christian worldview at every opportunity. Yet he remained apart. Malcom’s difficulties with the Catholic Church were a surprising combination of two things: 1) He was shocked and disappointed at the changes in the Church that seemed to have resulted from the Second Vatican Council. He saw religious life collapsing everywhere and moral teachings abandoned. 2) He was still a theological skeptic himself. Despite the post-conciliar liberalism that had no regard for doctrine, he was an honest man and would not join the Church if he didn’t accept its dogma. It’s not clear that he connected theological orthodoxy or liturgy with the moral precepts that concerned him. Nor is it clear that he worked very hard at theological understanding. This biographer suggests that Malcom was bored by theology. Although a reluctant moralist, he was fundamentally a poetic soul who seemed content with a mystical approach to the person of Jesus Christ.

Despite his distance from the Church, he began to call himself a Christian and tried to live like one. He established a daily prayer regimen. He gave up his womanizing, and further still, his drinking and smoking. He ate sparsely and became a vegetarian. He repaired his marriage to Kitty and tried to make things up to her. Their marriage became something beautiful and attractive, a hard-won prize. Their final years were spent in love, enjoying one another’s company and the company of friends, often reading the Pslams aloud to each other. Kitty would later write: “It is inevitable that in the course of time trouble and strife between man and wife should occur. This is for the most part due to our human vanity and egotism; but these differences can be overcome, and every reconciliation strengthens the bond of love.”

At long last, Malcom and Kitty received a letter from a respected priest and friend. In between formalities, the letter contained only one substantive line: “It is time.” Now 79 and 78 years old, respectively, this was all they needed. Malcom and Kitty Muggeridge formally entered the Catholic Church in November of 1982, finally at home and at peace. In July of 1990, Malcom suffered a crippling stroke. The state of his soul as a Christian penitent is manifest in the words he shouted that first night in the hospital: “Father, forgive me! Father, forgive me!” He died from complications four months later.